HOW AB TOOLS HAPPENED

BY ALAN BAKER

This has been in a thin notebook in our company break-room since 2009.

In September of 1953 Myrna and I were 25 years old and neither of us had a job. I didn’t have a degree or any learned skill with which to earn a decent living. We had about $300 in cash and normal debts. Myrna and I had been married 4 years, Jon’s older brother David, (who is next door at Robb-Jack), was 2 years old, we had some furniture, a car on which we owed more than the car’s value, and we were…totally defeated.

Myrna took David on a Greyhound bus from Warren, Pennsylvania to spend a few weeks with her parents in Missouri while I tried to find a job and a place to live. I wondered at times if she would want to come back to me. I drove two hours north from Warren to Buffalo, New York, because I’d seen newspaper ads for unskilled assembly workers at the Chevrolet-Tonawanda Engine plant. I told Myrna, “I can work on an engine assembly line as well as anyone.” I would’ve taken any job I could get. I drove early from Warren to be first in line at 8 AM on Monday, filled out their application, took a five minute timed test and ten minutes later the personnel man said, “We have an opening for a cutter grinder trainee on the swing shift.” It sounded like a question so I said, “Yes, Sir.” I found and paid a deposit on a tiny apartment, called Myrna to discuss how soon she could join me and went to work that Monday at 3:30 PM.

My First Job

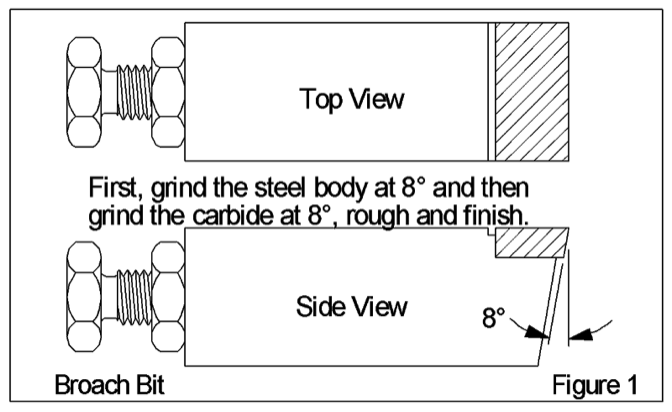

My first job was hand grinding broach bits. First I ground the steel away under the carbide, and then I rough ground the carbide edge on the vitrified green wheel, (which is now obsolete), then I finish ground the carbide edge on a diamond face wheel, sliding the broach bit back and forth on a table which was tilted to 8 degrees. After a few hours my fingers were sore from gripping the tools so hard, and I had blisters for a few weeks.

I didn’t make many friends with the other cutter grinders and on the way to my car one night the union steward told me that trying to outperform everyone else was causing some ill will. Then he said, “You better take it easy Baker, you could find your tires punctured some night.” Fortunately that never happened but I started trying to be friendlier.

A $50 Award

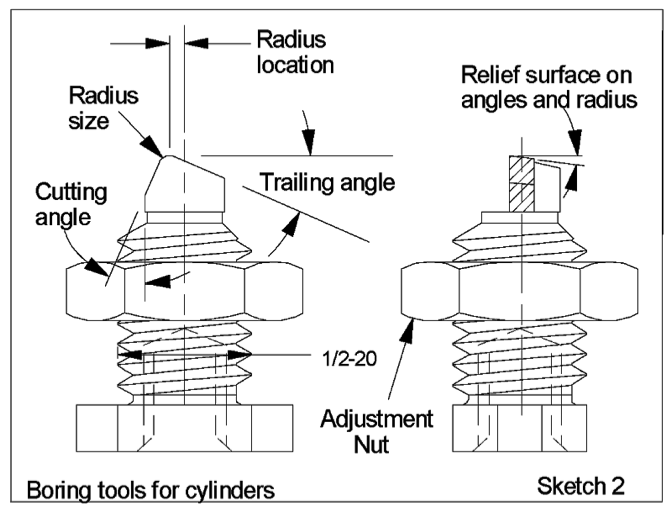

After six or eight months of sore hands, (my hands were much stronger than when I started) I started grinding the boring tools for the V-8 cylinders on a device that gripped each tool precisely as it was swung back and forth to grind the two cutting angles and the corner radius, shown on the sketch below. They finished the cylinders to size with a carbide tipped reamer.

After I had been grinding the carbide tipped boring tools for about four months I turned in a suggestion by filling out a form from the bulletin board, to improve the swinging device with an additional adjustment screw and stop. I got a $50 award, which was over two day’s pay, and in about a week the toolmakers had installed the new screw and stop that I had pencil-sketched. I was proud of it but there were no comments from my fellow grinders nor the supervisor.

We Can't Afford a New Skirt

Then Myrna worked days in an office at Bell Aircraft and I left David with a neighbor when I went to work at 3 PM, and Myrna got home at about 5 PM every weeknight. In those days secretaries all wore skirts and heels. We went shopping and found some nice wool skirts but they were $20 each. As we were leaving the store, knowing we couldn’t afford $20 skirts, there were some beautiful one-yard square wool remnants on a counter for only $1 each. I told Myrna, “I think I could cut up an old skirt that fits you for a sample, and make a skirt for $1 plus the zipper.” We had an old electric sewing machine that I found mechanically fascinating and still do; I had already made simple drapes by copying old ones. I made a skirt, she loved it and during several months I made seven more. A lot of my inside seams were sloppy but no one saw them except the dry cleaners and us.

My Second Job at Niagara Cutter

A skilled cutter grinder at Chevrolet told me that he had been working four hours a morning at Niagara Cutter, learning a lot, and that they were looking for another part-time trainee. After two years at Chevrolet-Tonawanda on the swing shift, I started my second job from 8 to 12 each morning at Niagara Cutter, where I learned to grind circular form tools. Myrna was happy to be a full time housewife and mother again.

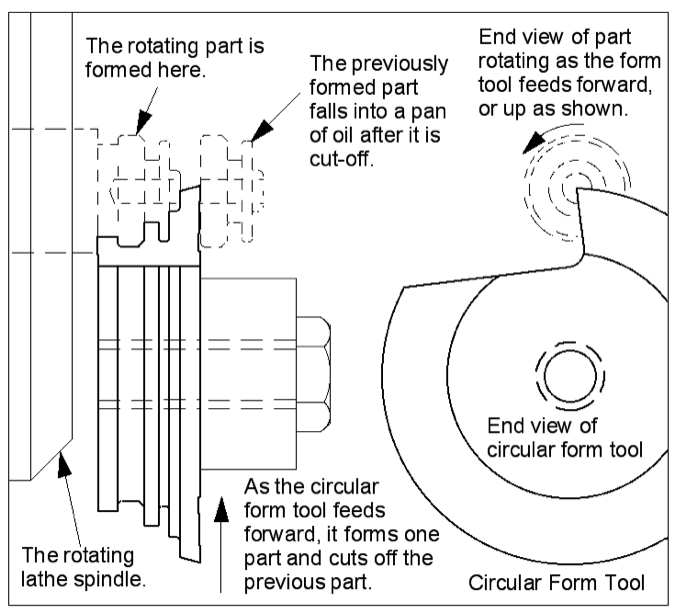

The HSS Circular Form tools were cylindrically ground, requiring lots of wheel changing and wheel dressing for every tool. You can see above how it is held in an automatic screw machine, forming one part as it cuts off the previous part. I also learned to grind flat form tools and swing corner radii on a Pratt & Whitney Radius Grinder. After working two months part-time Niagara offered me full time work at a slightly higher rate plus an hour of overtime a day, so I left my swing shift job at the Chevy plant. Our younger son, Jon was born in 1957, a year after I had started work at Niagara.

The Stupidest Decision I Ever Made

After two years at Niagara, with only a few years of grinding experience and no business experience…I started a business, Baker Form Tools. This was really dumb, the most stupid decision I ever made. I bought used machines on credit, mostly clunkers, rented a tiny shop and thought I could get orders by walking in with a business card. During my vacation week I rented a truck and took the machines to my rented shop, (a one-car garage plus a toilet), and told the owners at Niagara that I was quitting before I had made a sales call or had any idea how to get an order. (But I knew a lot of the customers’ names from their tool designs at Niagara.)

We were unable to pay our bills, so I took another swing shift job, grinding cutters at a different GM plant to help meet our debts. We had the normal expenses of a small family, and we were broke. After 2-1/2 years, with most of my shop bills paid, I sold Baker Form Tools to the company whose circular form tool business I had taken. I flew to Los Angeles, where Myrna’s sister lived and I applied for several jobs, with no luck at all.

15 Years of Intense Learning

Then I flew north to San Jose after calling Earl Weilmuenster, a good friend. He told me that Lockheed-Sunnyvale was hiring, and then he said, “My friend can get you an interview with the tooling people.” After a few frustrations we moved from New York to Sunnyvale and bought a nearly new $18,000 tract house in 1961 using the cash from Baker Form Tools plus a loan from my brother Owen for the $3000 down payment.

I started as a tool design trainee at Lockheed in a group of eight cutting tool engineers, all high seniority people who were skilled in various metal cutting applications. There were 12,000 employees. I learned a lot at Lockheed, about a broad range of cutting tools; end mills, countersinks, mill cutters, taps, drills, reamers, broaches, and lathe tools. It was the first of three five-year periods of intense learning and growth. I loved my work in every way. Ray Culver, my supervisor whom I admired, gave me the best advice I’ve ever had in my first annual review. He told me, "Alan, in working at Lockheed, 75% of your success will be based on getting along well with other employees and only 25% on your tool smarts." It took many years for me to learn that the same rule applies everywhere, in any job, in life! He also told me to take junior college classes, which I did, 2 or 3 nights a week for three years, even though we were busy working and raising our two sons. I completed 50 units, with mediocre grades, but I enjoyed learning and we gradually started being more liberal politically. About five years later Myrna took night classes at De Anza, while she was working full time as a school secretary, and she earned an AA with honors. (She studied, which I never did.)

In 1966, after having been promoted to a Senior Tool Engineer for about six months, I left Lockheed because National Twist Drill offered me a job as a service engineer, with a company car. I know now that my five years at Lockheed were just what I needed then. I tried to sell tools for almost four years total, with National Twist Drills and then with Brubaker Tools. Knowing I was a failure as an industrial salesman, I was defeated, again.

I started work for Robb-Jack in 1968, when they had about 15 employees. This became my second five-year period of intense learning. I not only learned a lot about cutters and applications but also about marketing and business. When I left there five years later I was learning about quotations, sales calls, business and marketing plus grinding cutters for at least half of each day. Bob Eitreim and Jack Peterson treated me more like a partner than an employee. I loved my work and my fellow employees. By then our older son David was earning a decent living installing headliners at the Fremont-Chevrolet assembly plant. During the model change-over he was going to be without work for one week and I asked him to come to Robb-Jack on Saturday. I taught him how to grind primary and secondary relief on a carbide end mill, plus the end gash and finish grind, with his hands, not mine. I hoped he would find it challenging, and he did, starting work at Robb-Jack on the following Monday and we worked together for one year. (He’s been the president of Robb Jack since 1998.)

In 1973 John Kern at FMC Ordnance persuaded me to come to work there because they were having big problems in the drilling of hard armor for the Bradley vehicles. I worked at FMC Ordnance in San Jose from 1973 through 1978, my third five-year period of intense learning. I was 45 years old but everyone there made it clear that I was a "new kid" among a lot of high seniority people. I annoyed several important people, forgetting what Ray Culver had taught me at Lockheed, “Getting along well with others is more important than tool smarts.”

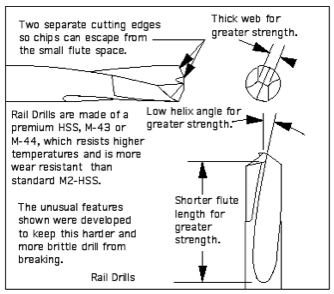

The problem job for which I was hired was the drilling of 1/4 inch thick hard armor plate for the Bradley vehicle. It was 4340 steel at 51 Rc which is too hard for regular HSS so they used solid and tipped carbide drills, which broke after a hole or two. There were big boxes full of broken carbide drills stacked around this huge machine, with a 12 by 30 foot table. The operator walked around on it, guiding the overhead drill motor. The hard armor plate was holding up delivery and everyone blamed someone else for being unable to drill the hard armor. It was a major shop stopper. I ordered Rail Drills, which no one there had ever heard about.

After they learned that I had ordered the Rail Drills several key employees let me know, emphatically, that “51 Rc steel can’t be drilled with HSS; only with carbide.” I had learned about Rail Drills on one of my trips to National Twist in Detroit, where I watched test cuts with different HSS grades in drilling a similar alloy steel with the identical 51 Rc hardness. Rail drills are made of special grades of HSS, M43 or M44, not the usual M2, so they can be heat treated harder, to 65 Rc instead of 62 or 63 Rc for the M2.

Alan's Expensive Rail Drills

But this extra hardness caused them to be brittle and have less torsional strength so the web shape is extremely thick, with shallow, short flutes. The Rail Drills solved the problem immediately…the hard armor drilling bottleneck was gone! (Rail Drills were developed for railroad tracks in the early 1900s.) The Rail Drills were run at a low RPM with a heavy feed rate, which I had observed at National, and the cutter grinders had no problem in regrinding the unusual split points. (My critics made sure that those boxes full of broken carbide drills disappeared, overnight.)

About two months after the armor plate drilling had been in successful production with the Rail Drills, Tony, the lead cutter grinder, called me and said, “Alan, come quickly to the big radial, the lathe shop manager had me grind a Rail Drill split point on a regular HSS drill and he’s going to prove that an ordinary HSS drill with that split point will work just as well, that we don’t need Alan’s expensive Rail Drills.”

I rushed to the machine and about ten people, including Bill Griffiths, the Chief Tool Engineer, were watching as the lathe shop manager replaced the 13/16 diameter taper shank Rail Drill with his modified regular HSS drill and started drilling the hard armor plate. The drill entered, sounded OK, but then it broke in the 1/4 inch thick hard plate, snapping with a frightening noise and sending drill pieces flying in several directions, but no one was cut. He disliked me more than ever.

After three to six months of testing them on various lathes I’d changed the steel cutting inserts in the lathe shop to a new carbide grade, with a new coating, which ran faster and lasted longer than their existing grades. Within a few years competitors had introduced their own new grades that competed with it but for about a year, it was “THE” industry grade for turning steel parts. (These inserts had upset the lathe shop manager.)

Introduction of Form Taps

My third cost savings was the introduction of form taps, saving thousands of dollars in oversize threaded holes and broken taps. They had transmission housings stacked near the machines where they were drilled and tapped, with rejection tags because of oversize threads or broken taps. When I asked Bill Griffiths, the Chief Tool Engineer, if I could order some form taps in small sizes he quickly replied…“No! Form taps are not approved in the H28 Handbook,” which I’d never heard of. I found the H28 handbook, dog-eared and yellow, where Form Taps weren’t mentioned. The H28 handbook on taps and threads was written by the Defense Department for World War II contractors, before the introduction of form taps in the early 1950. With my supervisor’s approval I had FMC’s Met-Labs run comparative tests, and they easily out-performed cut taps in aluminum. The Met-Labs engineers tapped 1/4-20 holes with both cut and form taps, then put a ground, heat treated steel thread gage in each hole and pulled on it until the threads in the aluminum part were stripped. It took 4100 pounds of tensile strength to strip the cut taps but it took 4350 pounds to strip the form tap threads, a 5% improvement. Yes, a bolt screwed into 1/4-20 threads in aluminum will lift a 4,000 pound car without stripping the threads! I still find that hard to believe.

After seeing the test results, and several discussions, Bill Griffiths approved form taps in 1/4, 3/8 and 1/2 sizes, in production, after which there were no more broken taps and no oversize thread problems. It took me about three months to prepare and initiate new work orders that defined the tap drill sizes required and how to gage form tap threads since the employees only had experience with cutting taps. This was probably a bigger cost savings than the carbide inserts I had introduced.

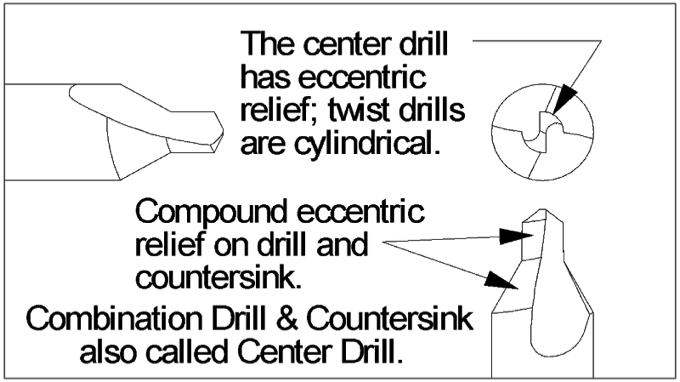

Shortly after the form taps were in production, and about 18 months before I left FMC, my boss frightened me by saying, “Bill Griffiths wants you in his office.” Bill was a grouchy guy but he chatted pleasantly for a few minutes and then he asked, ”Alan, if you scribed dimension lines on a steel part, and center punched holes at the intersections so small holes could be drilled, would you use a regular drill or would you use a center drill first?” I responded quickly, saying, “A center drill will drill the holes on the spindle centerline, so a twist drill, with cylindrical margins, should be used to follow the punched dimples.” Bill smiled and then he asked, “Why?” I told him “The center drill has eccentric radial relief on the diameter and it will bore a hole on the spindle centerline; it won’t follow the punched holes.” I got another big smile and he became quiet. As I walked back to my desk I was smiling too because I’d asked several machinists the same questions to learn if they knew that center drills have eccentric relief on their diameters, causing them to bore new hole locations. Two weeks later I was shocked with a big promotion. I became Bill Griffith’s Staff Engineer, with complete cutting tool responsibility in the 9,000-employee plant making the Bradley vehicles. My desk was next to Wes Hammond’s desk, a smart, important person with 20 years experience who supported me in every way.

24 Years and 9 Different Cutting Tool Jobs

After 24 years and nine different cutting tool jobs I finally had a job I was sure I’d keep until retirement. FMC was busy with long term Bradley vehicle contracts, I was proud of my assignment, I loved my work and I was finally starting to qualify for some retirement income. I learned later why Bill had put me in charge of cutting tools, which he’d always managed himself. He had cancer and knew he’d be retiring soon, and he died two years later. I’m proud to have worked for Bill. He knew more about metal cutting, welding and forming than anyone I’ve known and Bill was second in political power only to “Snoopy” Taylor, the late President of FMC Ordnance, who will always be one of my heroes.

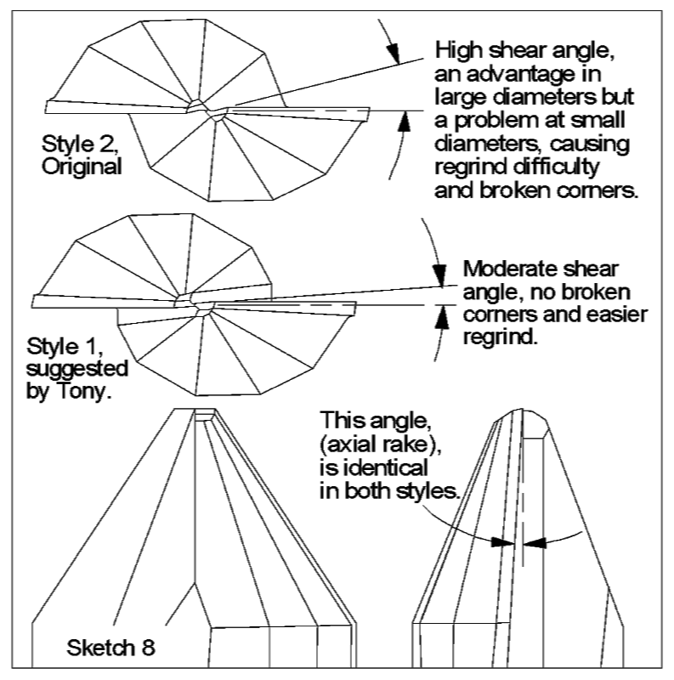

Tony, the lead cutter grinder at FMC, had shown me a problem he had with the HSS angle cutters they purchased to cut weld chamfers on the aluminum hull plates. See the next page. He told me he had contacted the manufacturer's representative and showed him how the high radial rake angle, at small diameters, was breakage prone and resulted in limited regrind life. He showed me some more of those cutters in 1977, telling me again about the breakage problems he was having, and telling me that he could not get any response from the cutter manufacturer, and Tony was angry. My mind was spinning...my only thought was, “I could make those cutters correctly if I had only a lathe, a mill and a cutter grinder.”

Those of you who have learned to turn, mill and grind the HSS F-Dash cutters know how important some of the end grinds were. Some high seniority employees may remember when making F-Dash cutters was about 30% of our business.

The Start of AB Tools

In April of 1977, at age 49, Myrna and I signed a 10-year, $30,000 second mortgage on our $65,000 house and started AB Tools. (Based on inflation data our $30K loan would be like $124,000 today.) This was more traumatic for her than it was for me, but we both knew we’d be paying on a huge mortgage for ten years if I failed. I bought 4 small machines and a cheap comparator. I rented a 14' by 24' shop in Santa Clara for $600 a month. I worked eight hours at FMC plus nights and weekends at my shop, getting small orders for specials through distributor friends.

During my one-year moonlighting period Myrna and I couldn’t have made it without our two salaries, making it possible to start AB Tools in a good cash position. I worked both jobs for about a year and then resigned from FMC and worked full time alone at AB Tools for about 10 months. When Myrna quit her school secretary job in 1981 she took her retirement money as a lump sum of $3000, which we invested in AB Tools.

My First Employee

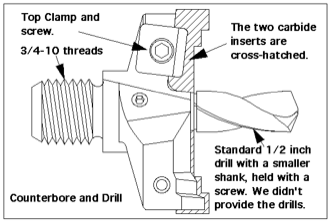

In early 1979 I got a huge order for 200 special carbide insert style counterbores for wood, shown below. David was happy at Robb-Jack and Bob Eitreim, the majority owner, was happy with David’s work. Jon was 21, operating a turret lathe in a small machine shop. After getting that big order I asked Jon if he wanted to be my first employee, which he thought about for a week…a long, anxious week for me. Then Jon worked patiently with me from early 1979 until I retired in 2003. During the first few years there were many days when we didn’t have enough work, so I made sales calls on distributors and machine shops, with single page flyers.

Jon had three complaints at AB Tools, the first one being the lack of details on customers' drawings. Senior employees know that the flute shape and number of flutes is usually our decision, not the customers’. It took Jon awhile to accept this because in making machined parts he knew every dimension, with tolerances. His second frustration was with collets. We ground the shanks from center holes. Then we ground the corner radii by holding the shanks in a collet but they were never concentric, so Jon asked if I could make a center device for the radius grinder. It evolved into the center devices we still use for grinding manually.

Our New Center Devices

Jon’s third frustration was the smeared floor finish he got when milling pockets with standard carbide tipped keyseat cutters, which we bought. So I ground side relief on some of those standard carbide keyseat cutters. Then he told me that a lot of the friends he’d worked with would be happy to buy carbide tipped keyseat cutters with side relief from us and suggested that we print a flyer. I took pencil sketches to a print shop that was already using the early CAD software. Then I took those one page flyers to distributors in the Bay area, after which we started getting orders for slotting cutters, mostly tipped at first, then solids, with side relief. About 25% of our business is still related to basic slotting and form cutters.

In addition to promoting our new center devices and suggesting ads for cutters with the side relief grind, Jon was more skilled at delegating than I was, so our management methods became more effective as the company has grown. David and Jon are both strong but caring managers.

Persuaded to Make Accu-Hold

In the early 90’s Mike Stewart of Coast Tools persuaded us to make our first Accu-Hold because Hewlett Packard had a new 60,000 RPM machine they were unable to use because of eccentric extension holders. It was a long struggle and we finally found the right way to make them, the opposite of our methods. After inconsistent quality when another shop was honing the Accu-Holds we bought our first Sunnen hone. Since then several key employees have developed the skills and gaging methods to make sure our Accu-Holds are always concentric. We even sell some to competitors because CNC machine manufacturers often ship them as accessories. The Accu-Holds are now 10% of our sales.

Introduction of the Shear-Hog

In about 1998 we developed our most successful product, the Shear-Hog. Based on our testing no other cutter has outperformed it in the cubic inches per minute of metal removal per HP, in aluminum. The Shear-Hog has two important features. The first is extreme sharpness and the other is ample chip-exit space. Jon still gets occasional phone calls from an excited machinist who wants to tell us how fast he is rough milling aluminum. Reducing a customer’s rough milling time from eight minutes to six minutes is a real savings, with no off-setting costs. Our inserts are expensive but with .030 to .040 thick chips, the insert life is exceptional.

The Most Important Thing That Happens

My job jumping was personally embarrassing. Having nine employers in 24 years is hardly something to brag about, but having so many jobs gave me a broad knowledge of the manufacture and application of cutting tools, plus...business, marketing and getting along well with others.

This is enough about how AB Tools happened. What is the most important thing that happens here every day, now? The dollar amount of new orders? The dollar amount of cutters shipped that day? Getting a raise? Getting a new customer? Having a record sales month? The most important thing that happens here every day is when you are grinding or inspecting the relief and rake surfaces on a cutter. IF those two surfaces aren’t perfect, and concentric, some customer will be unhappy.

Our final inspections might miss something that only the finish grinder or the inspector knows. What if one flute is .002 higher, or lower than the others…the person inspecting the tool could easily miss it.

We won’t be angry if you discuss an error, but we’ll be angry if we learn about the error from a customer.

Most of you have learned that if there is a bad dimension on a cutter, such as a .250 cut width being only .2493, this needs to be discussed and if the scrap versus ship-as-is decision reaches Jon’s desk he will try to get customer approval before deciding whether to ship it or start over.

With each of you inspecting another person’s work, instead of one inspector measuring every tool, this makes all of us more tolerant, since we all make mistakes. If there is a question or a problem…talk about it, now.

We’ll continue to be strict about attendance, punctuality and stretching our break times. My only proverb is, “Boredom is more tiring than hard work.” You’ve learned that the clock goes faster when you’re working hard.

We’ve needed and tried to keep our skilled, loyal employees with bonuses, health care, dental care and our profit sharing plan, which now totals $3.3 million. As owners, Myrna and I never took any of the company profit, which has been used only for new machines, bonuses and profit sharing.

If you’re expecting some personal advice from the old man…

Eat less, exercise more, work hard, make friends and save 10% of every paycheck.